A report outlining recommendations for the future of tertiary education has missed the mark in several areas where reform is most needed, writes Dr Kim Sawyer.

FOR 30 YEARS, government funding of higher education has been emasculated. In the 1980s, the Federal Government provided at least 80% of university funding, but last year the government provided only 36% of university funding. Governments of both political persuasions have privatised the public universities by stealth.

When we think of privatisation, we often think of British soccer clubs bought by a single owner, or public utilities that were privatised in the 1990s to become corporations with shareholders. The privatisation of universities has been different; nominally they are still public institutions without shareholders or owners, yet they operate like corporations.

The principal stakeholders, the students and the staff are not real stakeholders. They have little say in the governance. While the CEO of a public corporation is answerable to the board and shareholders of the firm, the vice-chancellors of many of our universities are unaccountable, except in a general sense. They have created governance structures that depend on them, rather than oversee them.

When I read the final report of the review into higher education (Australian Universities Accord), there was one word that I was looking for: bureaucracy. Yet it was never mentioned. Australian universities are like privatised bureaucracies. Academics are a species in decline — that is, the academics who teach courses, supervise research students and author research papers.

There is no better testament to that than the members of university councils, most of whom have not taught a course, graded an exam or supervised a research student in the last 20 years. The membership of the review committee was similar; all good people, all well qualified, but not qualified to review higher education. They are not the academics of lecture theatres.

The report made no reference to senior management or to the salaries of senior management. The vice-chancellors of Australia’s universities are the highest paid on average in the world, earning twice their Canadian counterparts. In 2022, 16 of them earned more than $1 million. In a recent survey, ‘79% [of] Australians agreed that vice-chancellor salaries should be capped so they are not paid more than the prime minister’, yet nearly all of them are.

Australian universities have become pyramids of inequality, where wage theft and casualisation co-exist with privilege, yet the report devoted limited time to the casual academics who underwrite the salaries of those at the top. The report recommended a tertiary education commission to oversee higher education. Its first task should be to address the inequality, but that’s unlikely. Almost certainly, the commission will become like a university council.

The Dawkins reforms led to an unregulated system with academics pitted against bureaucrats — and the bureaucrats usually prevail. At the time, I blew the whistle on misconduct at a university; another professor blew the whistle on financial misconduct at the same university. He later became director of the Cavendish Research Laboratory at Cambridge, a fellow of the Royal Society and one of the most cited physicists in the world. Yet both of us were forced out by a vice-chancellor who later became chair of the Australian Universities Quality Agency.

Academics are still pitted against bureaucrats, as the case of Professor Manuel Graeber shows. The 2001 Senate Inquiry, Universities in Crisis, recommended the establishment of a universities ombudsman to hear complaints from stakeholders, recognising that issues in universities required a dedicated ombudsman. The universities ombudsman was never enabled. The Accord recommended establishing an ombudsman, but only for students and not for staff. Academics remain out in the cold.

The Accord recommended doubling the number of domestic university students to 1.8 million by 2050 — 55% of people under the age of 35. Targets often tend to be flawed and this target ignores the evidence that many people do not want to attend university, preferring to learn through work experience, or attending technical colleges that are more practically oriented. The Dawkins reforms created a system too homogeneous — just ask any plumber or electrician. We need technical colleges of the past.

In 1991, Australian universities had 30,000 international students; in 2004 170,000 international students; and in 2023, nearly 800,000 international students enrolled in Australian universities. Nearly 50% of the students enrolling in Australian universities are international students. Australian universities depend on international students for their existence; as government funding declined from over 80% to 36%, so the shortfall was met by international students.

The dependence on international students is risky. Australia is more exposed than any other country to downturns in international education, like the one experienced during the pandemic. In 2018, the number of international students in Australia per 1,000 population was 17.9, a number that was nearly three times that of the UK, and six times that of the U.S. and Germany.

Our universities are addicted to international students, always seeking new source countries. Columbia, Brazil, Nepal and Vietnam, which were not on the universities’ map in 2004, have become their emerging markets. And there is always an unlimited supply from China and India. Having so many international students has created attendant problems; segmentation of students into particular courses, the English language issue and standardisation of curriculums. The Accord remained silent.

What was also not mentioned in the Accord is what should have been mentioned: standards. Standards matter. Australian universities have lowered their entry scores, passed students who should not have passed and traded off marks for money. There is no uniform national grading system and no national entry exam for graduate programs. Perhaps that would be too revealing.

Many Masters coursework programs, which have become cash cows of Australian universities, have lower standards than undergraduate programs, some would say lower than year 12 school. Measures could be implemented to measure standards, but they never will be.

A university is defined by scholarship, not fancy new buildings or glossy brochures. Many universities appear to believe that physical capital underwrites intellectual capital, ignoring evidence that many great ideas were not seeded in grand buildings, as Einstein attests.

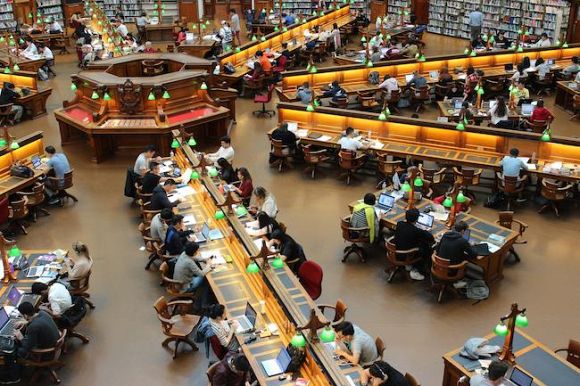

Scholarship requires students to be the independent thinkers we need, not the marionettes we may not need, for books in libraries to be stacked to the ceiling rather than hidden underground and for academics to discuss issues freely, without the sanction of management or donors. However, that was the old university and this is the new university of the Accord.

Dr Kim Sawyer is a senior fellow in the School of Historical and Philosophical Studies at the University of Melbourne.

Related Articles

- Universities Accord seeks to reform education and immigration policy

- Government report stresses need for reform on higher education

- The militarised university: Where secrecy goes to thrive

- Industrial scale cheating taking over from learning in Australian universities

- Higher education and the corporate mentality

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Australia License

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Australia License

Support independent journalism Subscribe to IA.